March 7, 2023

Just Put It on Our Tab

Our national debt has garnered a lot of attention this year, both for its absolute size and for the possibility that our elected friends in Washington might fail to raise its ceiling. In a way, it’s funny. In the same breath we voice concern over the amount of debt and even more concern that we won’t be allowed to take on more. Obviously, there are two issues at hand. The first is short-term in nature: Will Congress raise (or suspend) the debt ceiling and prevent the economic catastrophe that would accompany a US default? The second is longer-term: Is the country over-extended? Is $31.4T in debt too much?

Full Faith and Credit

As with any business or household, when spending exceeds income, debt is incurred to cover the difference. The federal government is no different. According to the Congressional Budget Office, in fiscal year 2022 the US government spent approximately $6.3T (about $200K per second!) but only received about $4.9T in revenue, primarily from individual income taxes and payroll taxes. We borrowed the $1.4T deficit, adding to the national debt.

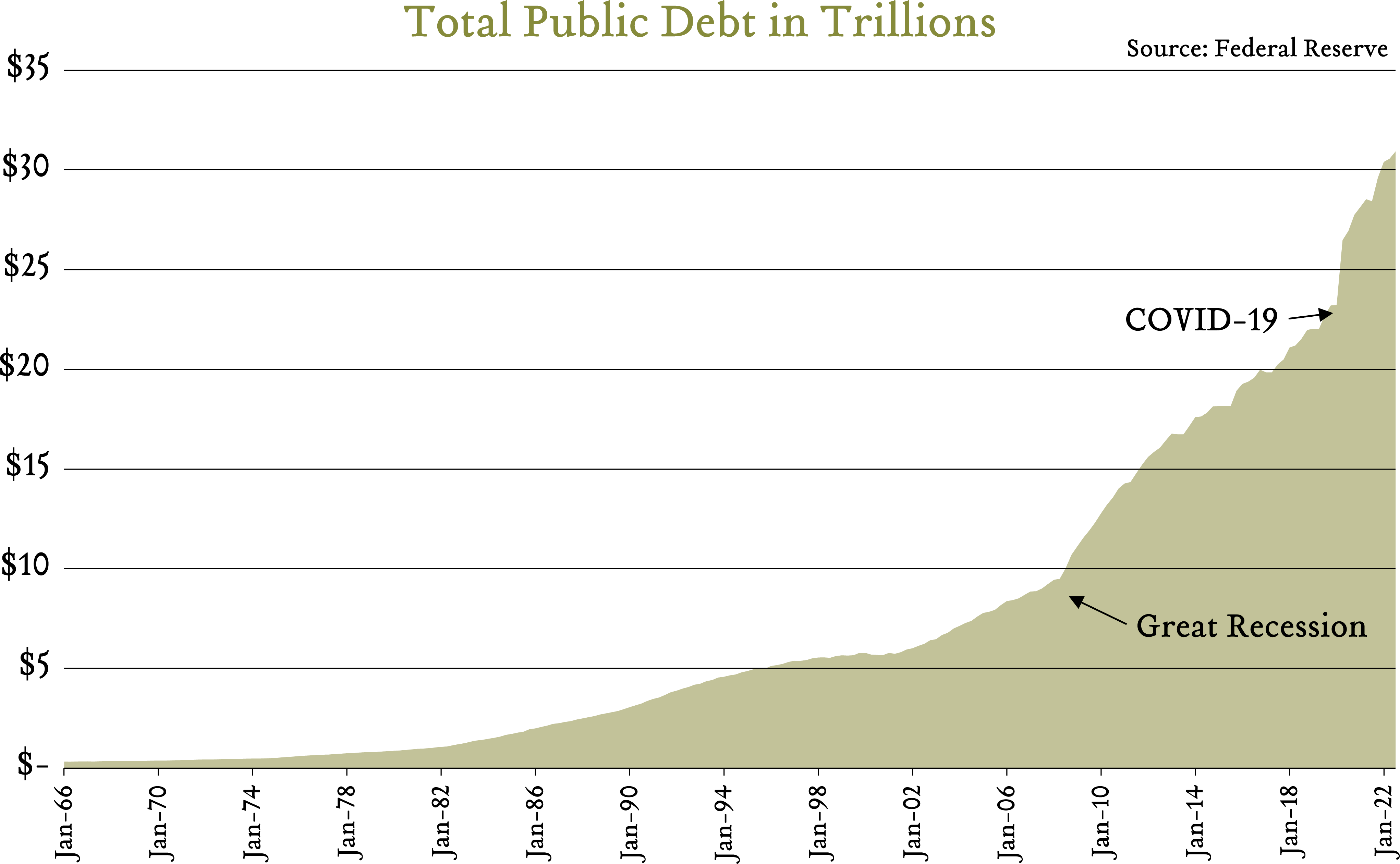

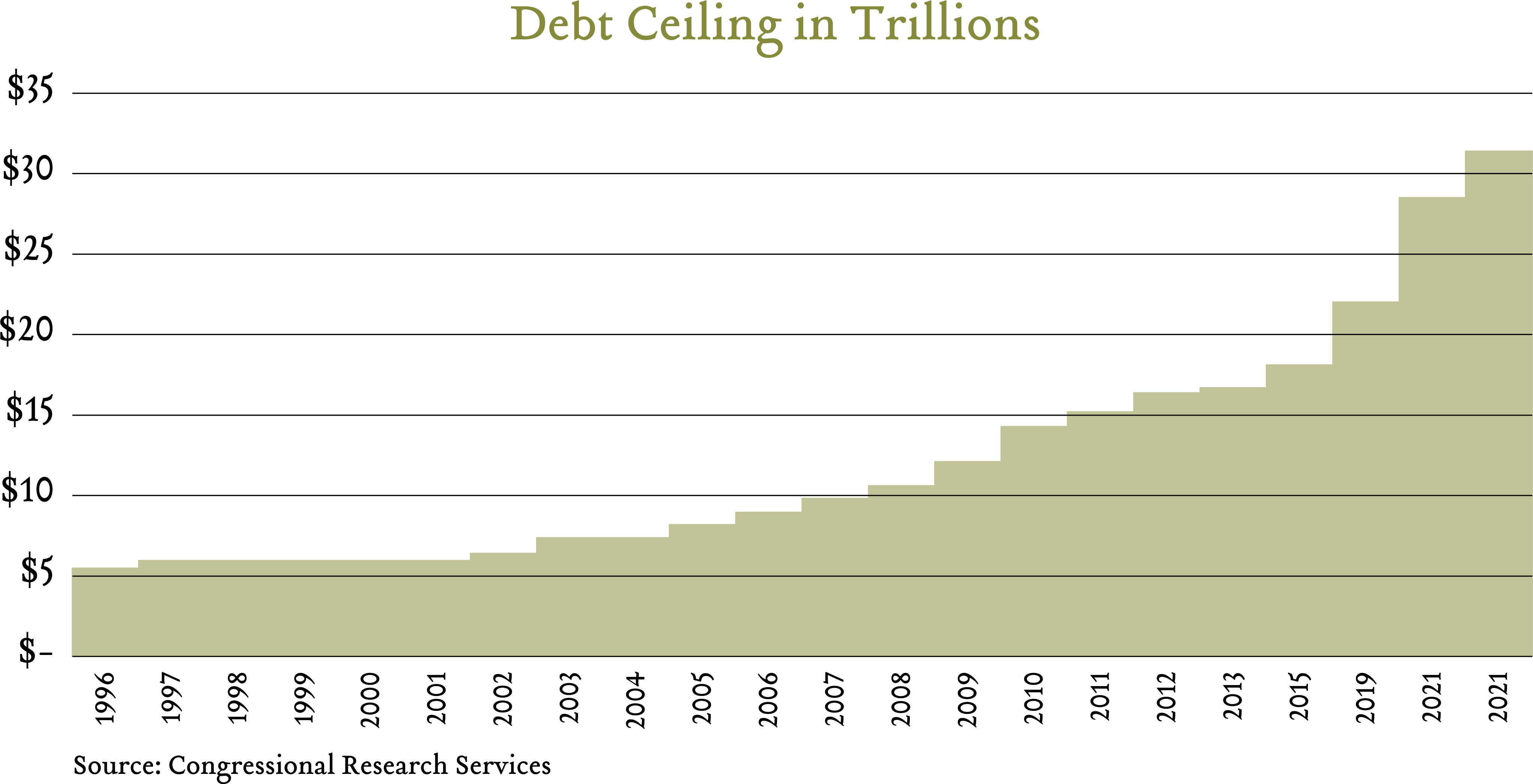

Since the onset of the pandemic, the national debt has increased by $7.3T or about 30%. Congress limits the total amount of money the government can borrow with a so-called debt ceiling, which stands at $31.4T. We reached this debt ceiling in January, which means the US government is currently unable to borrow incremental funds to cover debt service and government-funded programs. Fortunately, it doesn’t have to… yet.

For now, the US Treasury is using “extraordinary measures” to buy some time until Congress can reach a deal to increase the debt ceiling. These extraordinary measures are really just accounting maneuvers that enable the government to pay bills with cash it already has on hand, even if said cash was earmarked for other purposes. US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has estimated that the X date, or the date the Treasury runs out of options and a default occurs, is somewhere around June of this year. Meanwhile, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects a default date sometime between July and September, if not earlier based on the actual amount of tax revenue received in April. Congress will need to raise (or suspend) the debt ceiling prior to the X date in order to avoid a default on our nation’s debt.

Brinksmanship

Renegotiations of the debt ceiling are historically common and typically have not been very contentious. According to the US Department of the Treasury, Congress has acted 78 separate times since 1960 to permanently raise, temporarily extend, or revise the definition of the debt limit. This means that on average the debt ceiling has been renegotiated every ten and a half months, more than once per year, since 1960.

So why all the hubbub this time? Heightened concern stems from doubt that a divided Congress will be able to reach a compromise. Following the 2022 mid-terms, Democrats continue to control the Senate, while Republicans now control the House. House Republicans, seeking concessions on spending from Democratic legislators, are using the debt ceiling as leverage. Democrats, for their part, have publicly stated that they are not willing to negotiate and that the fate of the nation’s full faith and credit depends on Republicans’ willingness to drop the debt ceiling as a bargaining chip. With both sides talking past one another, it is no surprise that we find ourselves in this predicament.

In the worst-case scenario, neither party concedes, the debt ceiling does not get renegotiated, and the US government defaults on its liabilities. This would obviously be catastrophic for financial markets and the broader global economy. Historically, and in spite of a few close calls, Congress has always managed to find common ground on this issue. Based on the stakes, Congress and the president have every incentive to avoid this worst-case scenario, and it is for this reason that we believe a deal will be struck prior to the X date.

In addition to raising the debt ceiling before the worst comes to fruition, we also predict a fair amount of political grandstanding by legislators and dire warnings from news pundits over the next few months – all of which should be taken with a grain of salt. While the risk of a default by the US government is real, the probability of it occurring at this juncture is small in our opinion. Instead of taking jabs at one another, we would prefer to see both parties put their differences aside and come to the table sooner rather than later to get this issue resolved.

Up to Our Eyeballs?

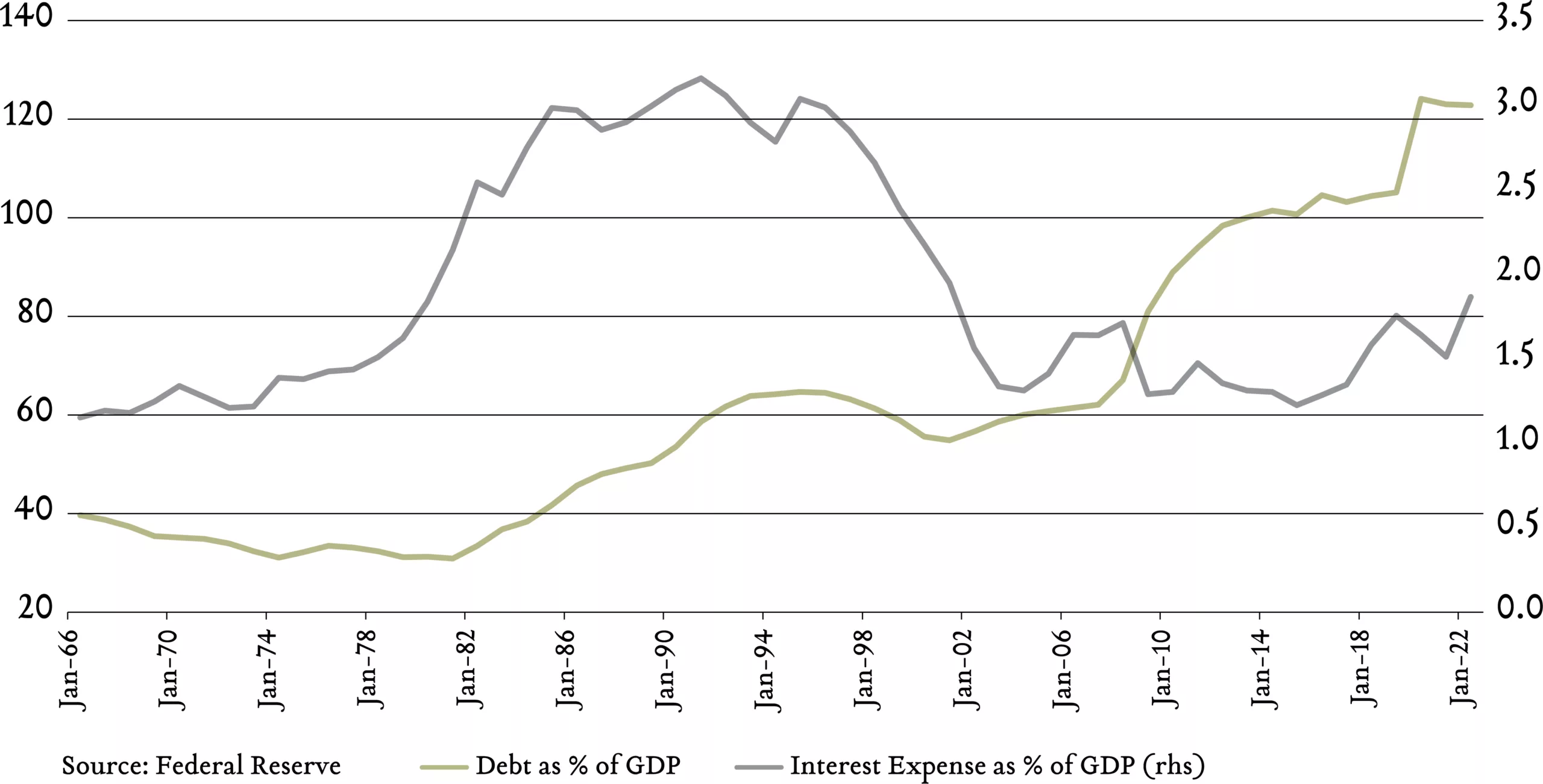

Now let us turn our attention to the slower-moving, longer-term $31.4T elephant in the room. As illustrated in the first chart, US debt has grown from $320 billion in 1966 to over $31 trillion today – a 9,000% increase. These are large numbers, but they ignore two important factors. The first being the growth of the overall economy, and the second being the government’s ability to pay the interest on its debt. The accompanying graph shows how the debt has grown in relation to the size of the economy, as measured by Gross Domestic Product (GDP). The graph also shows how the debt servicing costs have changed over the years in relation to GDP. We use GDP here as a measure of the US economy, which is directly linked to the ability of the US government to generate revenue through taxation.

The level of debt in relation to the size of the economy has risen from 40% of GDP to 120% of GDP. However, the cost for the government to service its debt in relation to GDP, while higher than it was in 1966, is actually lower today, roughly 2% of GDP, than it was in the 1980s and 1990s. This illustrates that the US is not overly burdened by debt service costs at this time; however, with the rise in interest rates we expect to see the servicing costs increase in future periods.

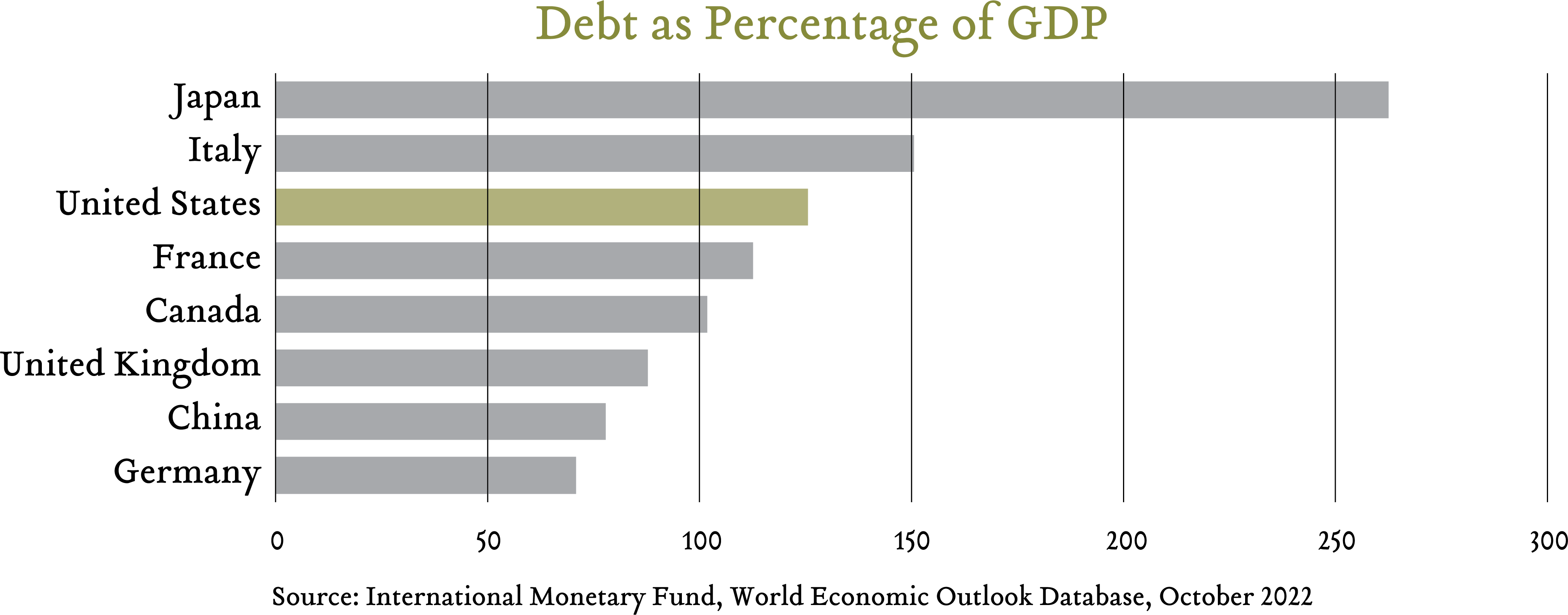

If we zoom out and view the US government debt in relation to the G7 nations plus China we see that our position is not unique. Increasingly, governments around the globe have grown their balance sheets in order to finance social benefits, combat recessions, and bolster military spending.

The US government has many advantages compared to its global peers. The US is the world’s largest economy. It is also the sole issuer of the world’s reserve currency. These advantages, in our opinion, provide the US with flexibility to address its debt challenges before they become a significant economic concern. This is a slow-moving problem at the moment. However, should the US experience economic stagnation, high interest rates, and a similarly large expansion of debt over the next 60 years, our opinion would be subject to change.

Conclusion

In the short term, the US government has reached the borrowing limit imposed by Congress. While brinksmanship and grandstanding will likely fill the air time between now and the eventual X date, realistically, we view the likelihood of a US default as a distant tail risk. For the time being, we believe national debt levels are manageable in the context of our nation’s GDP and ability to make interest payments. Longer term, there is a limit to how much money our government can borrow, but it will likely be determined by market forces, not necessarily by Congress.