October 7, 2024

Have a Taxable Estate? Gift Today – Exploring the Tax Inclusive Nature of the Federal Estate Tax

For individuals and families who have accumulated significant wealth that may be subject to an estate tax at their passing, the decision on how and when to pass on the wealth may be difficult. Concerns typically range from worrying about the loss of control of the assets to how the gift will impact the recipient’s motivation to be a productive member of society in the future. This article will not attempt to alleviate those concerns, nor will it provide details on any of the various estate planning techniques that have been explored in previous articles. In this article, we will explore whether it is financially beneficial to gift during your lifetime as opposed to at your passing due to the tax exclusive nature of the federal gift tax.

Inclusive vs Exclusive Tax: The federal gift tax is tax exclusive unlike the federal estate tax, which is tax inclusive. The recipient of a gift does not pay the tax. Instead, the tax is paid by the donor either paying gift tax or using up a portion of their exemption (tax exclusive). Whereas the recipient of funds from an estate must use those funds to pay the estate tax (tax inclusive). Consequently, even though the stated federal gift and estate tax rates are the same, 40%, the effective gift tax rate is about only two-thirds of the effective federal estate tax rate. Translated, a donor may give more to the donee by making a lifetime transfer rather than using a testamentary transfer. In addition, any future appreciation of the gift, and the income generated by the gift, happens outside the donor’s taxable estate.

Effective January 1, 2024, the federal estate and gift tax exemption is $13.61 million per individual. As the 2026 sunset date for the current estate tax structure looms on the horizon, many discussions will take place regarding whether an individual should make lifetime gifts to use the donor’s unused applicable exclusion amount, to pay the gift tax now, or to delay transferring assets until the donor’s death. One important consideration in those discussions is whether the transfer will have carry over basis, as with a gift, versus a full income tax basis step-up on the transferor’s death. The basis discussion should also include the tax exclusive nature of the federal gift tax.

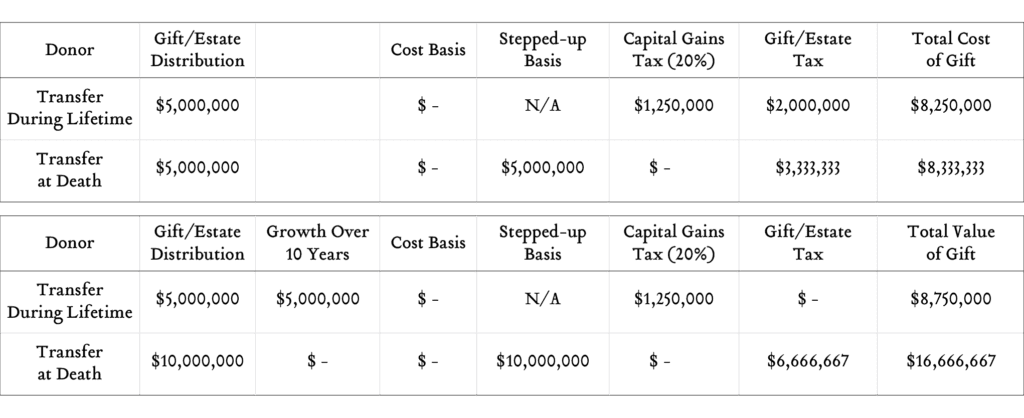

George Bearup, a Senior Trust Advisor at Greenleaf Trust, often uses an illustration to explain the difference between the two transfer taxes and quantify the difference. The following example is simplified for illustrative purposes and assumes that liquidity is available to make the gift and pay the tax. Additional factors that would need to be considered to determine the full impact of gifting during life versus at death include liquidity, asset basis, potential growth, etc.:

Don asks his advisor whether he should make a lifetime gift of $5.0 million to his daughter or wait and pass that same $5.0 million to his daughter at the time of his death, i.e., a specific bequest under his Will or trust of $5.0 million.

If Don gives his daughter $5.0 million as a gift, using the 40% marginal federal gift tax rate, Don’s gift tax will be $2,000,000 [$5.0 million * 40%]. As the donor, Don will pay the gift tax, which results in Don’s daughter receiving the full $5.0 million and an additional $2,000,000 removed from Don’s taxable estate. In short, it costs Don $2,000,000 to give his daughter $5.0 million. If Don has exemption remaining, it costs Don $0.00 to make the gift.

If Don waits until his death to make the $5.0 million bequest to his daughter, it will take a bequest of $8,333,333 bequest to leave his daughter $5.0 million [40% of $8,333,333 = $3,333,333 in federal estate taxes, thus leaving a net amount of $5.0 million for Don’s daughter.]

The result is that it will cost $1,333,333 more to give Don’s daughter $5.0 million at Don’s death via a bequest than during Don’s lifetime with a gift.

Another way to analyze it is that there is a 40% federal estate tax on the bequest of $5.0 million ($2,000,000) and then a subsequent tax of 40% on the amount that Don’s estate used to pay that $2,000,000 federal estate tax ($800,000); then that $800,000 faces its own tax of 40%, resulting in a further tax of $320,000, and so forth. This results in a geometric series in which the ratio is the 40% federal estate tax. The formula for the sum or a geometric series is (initial amount)/ (1-ratio). Here, ($5.0 million)/(1-40%) = $8,333,333, so the total estate tax on a gift of $5.0 million is $3,333,333. Please note that the capital gains tax has also been calculated using the same formula above and a 20% long-term capital gains tax rate.

Gifting is not as effective if the donor is not expected to survive. The gift tax on transfers made within three years of the donor’s death will be included in the donor’s gross estate for federal estate tax purposes. [IRC 2035(b).] Accordingly, if Don dies within three years of his gift to his daughter, the $2,000,000 of gift taxes that Don paid will be included in Don’s estate, thus negating the differential of how gift and estate taxes are calculated. Any post-gift income and appreciation on the gifted assets will continue to pass federal estate tax free on Don’s death.

The payment of the gift tax reduces the investable asset base within the portfolio and reduces the compounding that can occur. In the example above, the investable asset base would be reduced by $2,000,000.

Summary: There are many considerations behind the decision whether to make a lifetime gift or delay that transfer of wealth until the donor’s death. While both the federal gift tax and the federal estate tax carry the same 40% tax rate, it is important to remember that the effective transfer tax rates for each are much different. The complexity of this decision encourages the collaboration of your team of advisors to make certain you are accomplishing your goals in the most tax efficient manner.